i've been thinking about elaine riddick

forced sterilization, eugenics, and shame-based health care: american as apple pie

CONTENT WARNING: Discussion of forced sterilization, medical racism, eugenics, plantation science, medical abuse, slavery, and more.

This essay is likely as much of a doozy to read as it was to write— however, it’s a necessary one. U.S. history is disgusting and horrifying, and it’s also (for us Americans) our story.

It’s yours to read: be not afraid of what you’ll find.

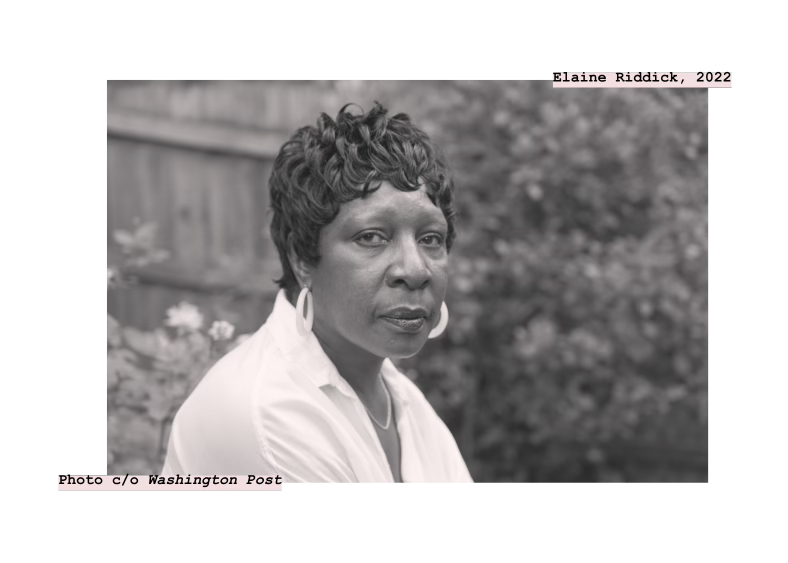

“The doctor told me that I had been butchered.”

These chilling words—spoken by 70-year-old North Carolina native, Elaine Riddick, in conversation with CBS in 20111—are unfortunately shared sentiments between victims of the United States’ forced sterilization projects in the 20th century. Despite the positive spin that White, male doctors gave their eugenic practices at the time, the harrowing stories of whistleblowers like Riddick challenged the dominant narrative of population control as a societal benefit. Rather than White doctors providing underprivileged women with needed family planning, it was the Black, Indigenous, Puerto Rican, Mexican-American, and all disabled women violated by forced sterilization whose stories finally exposed the truth. “Population control” was an effective ruse for the non-consensual, race- and class-motivated sterilization of hundreds of thousands of women across the United States, resulting in a painful legacy for poor, racialized, and disabled women seeking reproductive health care today: one of lineages cut short and reproductive justice denied.

How then, could an experience like Riddick’s be passed off as a social good? How could doctors feasibly convince the parents of a 14-year-old rape victim that the forced sterilization of their daughter was a benefit not only to broader society, but to their daughter?

I argue that neither Elaine Riddick nor her guardians were convinced of the benefits of her sterilization, but rather forced into silence by doctors wanting only one answer: Yes. Using the dual forces of shame and fear, state governments, individual health care providers, and their surrounding communities can have a silencing effect so powerful, it enables mass atrocities like the forced sterilization of Black women in North Carolina. In Elaine Riddick’s case, she was failed by her close relationships, her health care provider, and the state of North Carolina: all of which used shame and fear around sex, sexuality, and reproductive medicine to forgo Riddick’s agency, resulting in her forced sterilization at 14.

Stereotypes Around Black Sexuality

When the Eugenics Board of the State of North Carolina chose to sterilize Elaine in 1968, they cited her being “feebleminded” and “promiscuous,”2 both of which gave them the right under Buck v. Bell to override her consent. The latter term was placed on Elaine because of her status as a rape victim; she had been molested and impregnated by a man in her neighborhood, a decade her senior.3 While unfortunate, the lack of compassion for a child in Elaine’s circumstances is, sadly, unsurprising. Even before her violation, the cultural environment around sexuality in North Carolina—especially in the small town of Winfall—was one encouraging feelings of shame and fear, especially in Black children. According to Riddick herself, “nobody ever told us about having babies—that was never discussed around us.”4

In Johanna Schoen’s Choice and Coercion, she describes a North Carolinian medical system intent on sterilizing any Black girl who was sexually active, as they felt that gave them evidence to label her the necessary “feebleminded.”5 Unfortunately, “sexual behavior, race, and class background constituted major factors in the identification of the so-called feebleminded.”6 There was a societal concern about “sex problems” generally, but Black girls were (and continue to be) treated as adults where White girls were treated as girls.7 This is considered adultification bias, which leads to Black girls being considered less innocent (therefore less in need of care) than their White peers.8 This harmful stereotype presented itself in the sterilization programs in North Carolina; “A concern with sexual behavior led social workers to focus on those whose deviation from the desired norm was particularly obvious or disturbing: sexually active single women.”9 The cases of Black rape victims fell into the hands of these same social workers, who not only approved, but actively sought the forced sterilization of over eight thousand people between 1929 and 1975, under the North Carolina Eugenics Board.10

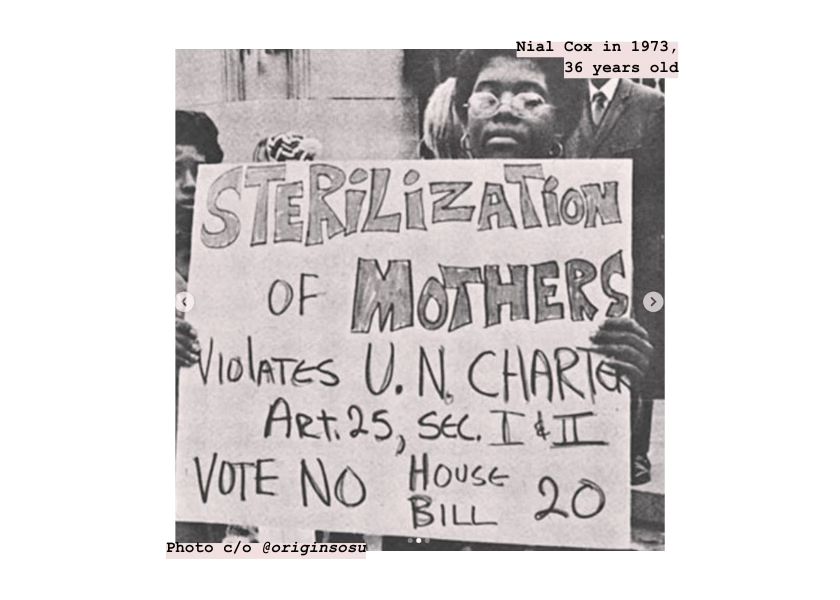

One of these women was Nial Cox, who at 18 underwent a forced sterilization under that same Eugenics Board, all due to her being an unwed, Black mother. She, too, was labeled “feebleminded,” and her social worker, Shelton Howland, insisted on her sterilization to the point of coercion following Nial’s routine contact with the welfare department.11 Despite Nial being 18, a surgeon’s discharge described her as “An eighteen year old mentally deficient girl” [Italics mine]; this hypocritical view of Nial as more adult yet also a girl to be controlled allowed for further paternalism from North Carolina. Due to her labeling by the state, the decision to sterilize Nial came down to her mother, Devora. “If Nial and her mother refused, Howland threatened, Devora and Nial’s siblings would all be stricken from the welfare rolls. Faced with the loss of her entire income, Devora finally consented.”12 Except, Devora didn’t consent—she was coerced and financially manipulated by her social worker and her local social services office, resulting in the nonconsensual tubal ligation of Nial Cox. Unfortunately, the Cox case was standard in sterilization cases in North Carolina; “The link between mental deficiency and sexual immorality seemed especially close in the case of African American welfare recipients.”13 This eugenics-focused environment set the stage, sadly, for Elaine Riddick’s violation.

Elaine’s experience of sexual violence as a child resulted in her being labeled by the state “promiscuous” and unable to get along with others.14 But in Riddick’s words to NPR, "I couldn't get along well with others because I was hungry. I was cold. I was a victim of rape.”15 But her social workers did not see her or her family as worthy of protection; they decided to use sterilization as a Band-Aid for the finances of the welfare system, therefore treating Riddick and all those sterilized by the North Carolina Eugenics Board as less than human. Elaine was not sexually active by choice, but she was treated just the same as Nial Cox; with the use of shame by labeling her “promiscuous,” therefore “feebleminded” (which takes away her legal agency), then using the fear of losing welfare benefits against Elaine’s mother, Devora, to force her consent on-paper for her daughter’s sterilization. It was this institutional shame and fear about sexuality, even for a rape victim, which enabled a 14-year-old girl to awaken from her birth with bandages on her stomach—and no one to explain to her why.16

Race, Class, and Consent

Elaine Riddick was not formally told that she had been sterilized until 2007, when a doctor told her she was “butchered”—he was referring to the cutting and cauterizing of Elaine’s fallopian tubes just after she gave birth to her first and only child.17 However, this practice of complete nonconsent was average in the sterilization programs across the United States. Not too far away in New York, one physician admitted, “The best time to make a pitch for sterilization was when a woman was groggy from anesthesia.”18 Therefore, consent was not only not requested, but not desired of Black mothers on the delivery table, who were silently sterilized using shame- and fear-based stereotypes about Black and poor mothers. This system allowed for the bypassing of Elaine Riddick’s informed consent when sterilized by the state of North Carolina.

North Carolina—its social workers, social services departments, and Eugenics Board—was consistently on the hunt for single, Black mothers who collected welfare benefits to sterilize. Given that their consent was wilfully bypassed, the social workers who sought these Black girls’ and women’s sterilization were buying into a set of biases in order to “save” the state from allocating welfare funding to growing, poor families. Especially when a mother was Black and single, the state felt they had a vested interest in keeping the mother from having more children, therefore creating a greater (by their words) “burden” on the welfare and medical systems.19 Throughout North Carolina, according to Johanna Schoen, “Class and race [were] factors in the identification of potential sterilizations cases.”20

In the search for “feeblemindedness,” social workers fell on harmful stereotypes of hypersexuality and White supremacy to legitimize their selection of a Black girl or woman for sterilization. And unfortunately, social workers had a large amount of power in this selection process; North Carolina’s “sterilization law was the only one in the country that permitted welfare officials to petition for the sterilization of their clients.”21 This allowed individual White people, empowered by the state of North Carolina, to enact population control and attempt to keep Black and poor people subordinate via reproductive violence. They weaponized the fear of loss of benefits or the induced drowsiness of a delivery—as was the case with Elaine Riddick—to game consent.

Social workers had a particular focus on single Black mothers. While stereotypes about the Black family (branching from legacies of chattel slavery, Jim Crow, then The 1965 Moynihan Report)22 aided in their justification of potential sterilization cases, “Presence of children outside the marriage served as an indication of women’s emotional immaturity and mental retardation.”23 Even if these women (like Nial Cox) were mothers, their being single-yet-sexually-active was enough of a start for the eugenics-hungry social workers of North Carolina to justify their sterilization cases. Here lies the true paradox of White supremacist projects like eugenics: they are built on subjectivity and pseudoscience. Even when there is an attempt as systematization, as many sterilization manuals for White doctors24 or questionnaires for White social workers25 at the time did, it was all based on the subjective authority of the White gaze. Because of the individual beliefs and invented justifications of White social workers, girls like Elaine Riddick were intimidated, shamed, or fibbed into a procedure which served much bigger—and much more sinister—purposes.

A plane ride away in Puerto Rico, the same eugenicists of North Carolina had exported their ideology to the island, which U.S. capitalists believed was about to undergo a “population explosion.”26 Despite the United States’ continued colonization of Puerto Rico (or Borinquen), the 20th century brought changes for Puerto Ricans; in 1917, Puerto Ricans became U.S. citizens,27 and in 1952, the Puerto Rican Constitution was approved by Congress and Puerto Rican voters.28 This increased interaction between the U.S. and Puerto Rican citizens brought increased emigration to the United States, leading to a racist panic from White Americans.

They saw the large families and mothers in Puerto Rico just as they did Black families and mothers: a “drain” on the United States. “Some doctors claimed that Black women, Puerto Rican women, and Native American women were more fertile than White women.”29 This translated into reproductive violence via the widespread insistence on La Operación for Puerto Rican women, as well as the non consensual use of Puertorriqueñas as test subjects in the development of new birth control technologies.30 The fear of White Americans ended up rendering many Puerto Rican women sick, infertile, or damaged where they otherwise would not have chosen to be, validating, for the eugenicists, the lack of consent from the women they tested on.

This example, along with the story of Elaine Riddick, exemplifies how shame-based stereotypes, influenced by race and class, were used to stoke the necessary fear to sterilize a poor, racialized girl or woman. While the struggles of Puerto Rican and Black women differ, both populations have experienced the consequences of the loss of their consent at the hands of the U.S. government and their various sterilization projects.

Invisible Pain, Invisible Girls

Because Elaine was not informed of her tubal ligation at the time of her delivery, she grew up expecting to have a normal life, including having more children once she felt ready. “I got married when I was 18, and my husband and I tried to start our own family,” Riddick recounts to CBS. “Prior to that, I kept getting sick. I kept hitting the floor, falling, passing out.”31 Despite the fact that Elaine felt ready to become a mother to another child, her mind and body were silently dealing with the trauma of her tubal ligation. Even before trying for another child, Riddick told The Washington Post that she felt, essentially, robbed by the aftermath of her sterilization: “I didn’t have a childhood because of the hemorrhaging and passing out. This is how badly they damaged my insides.”32

It was only after one of these many episodes that Elaine was finally told the truth; she had been forcibly sterilized by the North Carolina State Board of Eugenics at 14, and she could not have any more children. Not only that, but her consistent health issues had a root cause; the cutting, tying, and cauterizing of her fallopian tubes at such a young age.33 The silence that accompanied Elaine’s pain and health struggles was, unfortunately, yet another symptom of the racist, classist design of the U.S. medical system. Similar to the adultification bias Elaine and other Black girls face as children, Black girls and women experience medical racism via under-treatment and under-diagnosis, largely due to the legacy of the “father of modern gynecology,” J. Marion Sims.34

In a parallel to the experiences of Puertorriqueñas, James Marion Sims—an early American gynecologist in the mid-1800s—was engaging in experimental gynecological work. To test his new theories and rudimentary technologies, Sims used the bodies of enslaved Black women in Alabama—their names were Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsy.35 Sims performed cruel experiments on these women without ever using anesthesia, requiring thirty different surgeries on Anarcha specifically before finding success in the repairing of her vesico-vaginal fistulae.36 It is from these very experiments that American gynecology was born, and despite his crude, horrifying tactics, Sims was made the president of the American Medical Association and the American Gynecological Association just before the turn of the century.37 Sims’ unfortunate leadership established a discipline whose very foundations believed Black women to feel less pain and deserve less care than their White counterparts.

Harmful stereotypes about Black women and their bodies also originate in plantation science, as illuminated by Dr. Symphony Fletcher of the University of Chicago. Dr. Fletcher shared that, on plantations, White doctors and enslavers recorded Black women as having a more narrow pelvic size than that of White or non-Black women—this practice is called pelvimetry, and is based in eugenic science.38 In fact, just 34 years before Elaine Riddick’s sterilization, the Coldwell-Malloy classification system for the pelvis was introduced to gynecology textbooks—some of which are still in use today.39 This system classified pelvises into four categories: “Gynecoid” (woman-type), “Android” (man-type), “Anthropoid” (“ape-like”), and “Platypelloid” (flat-type).40 Sadly, Black women like Elaine were considered to have an “Anthropoid” pelvis; one slightly more narrow or shorter in stature than what White doctors considered to be the norm. This is a direct reference to the racist caricature of Black people as apes, which dates back to early colonization and was spread as a way of establishing the superiority of European people.41 This racist association has grown into a variety of harmful stereotypes about Black women’s bodies and birthing experiences, including Black women being more fecund, more robust, having a more flexible pelvic floor,42 and being able to withstand more pain than White or non-Black women.43

Today, these stereotypes have manifested in the reduced offering of epidurals during childbirth, more traumatic pregnancies and deliveries, and ultimately, the unnecessary and tragic death of Black women when birthing. It is this medical racism which led to the current maternal mortality crisis in the United States, which primarily affects Black women, and it is these stereotypes which led to the silencing of Elaine Riddick in the aftermath of her sterilization. While Elaine needed the care of the medical system, the lack of attention paid to Black women’s pain and agency—both historically and in her birthing experience—drove her into silence. Rather than seek out help for her continual hemorrhaging and passing out, Elaine recognized herself being safer outside the walls of the North Carolinian medical system, even if it did rob her of her childhood. In this way, the harmful stereotypes about Black women’s bodies led to Elaine being driven away from seeking medical attention, all relating back to shame and fear, and resulting in poor health outcomes.

Lying “for the Common Good”

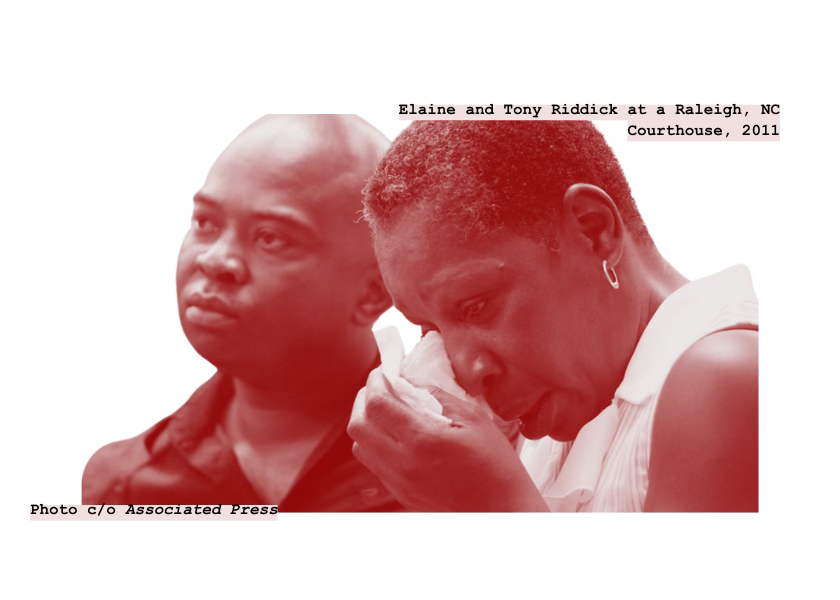

“Then I realized I was sterilized, because he explained to me what happened,” said Elaine Riddick of the second doctor who, in 2007, told her she had been “butchered.” This doctor, however, walked her through exactly what had happened to her fallopian tubes. “I tried to have it reversed, but it never worked.”44

In Riddick’s story, there is a consistent lack of honesty and specificity between provider and patient. The procedures Black girls were subjected to were never fully explained—to patients or parents—and many walked away believing they could get pregnant again, or the procedure could be successfully reversed. While White doctors can hide behind lack of written record, as admitted by indicted physicians in a California lawsuit on behalf of ten Chicana women who were forcibly sterilized,45 voices of victims can challenge this medical and historical silence. Through their stories, we’re able to understand the societal shame and fear used to coerce these girls and women into being sterilized, and the lack of information they were provided—before and after their procedure.

Particularly for Black girls in North Carolina like Elaine, this campaign of coercion ramped up as the state’s eugenics program intensified their pressure on social workers to locate potential cases so to cure society’s ills. Furthermore, the development of eugenic thought brought new (false) justifications for those enacting population control and forced sterilization. As discussed by Johanna Schoen in Choice & Coercion, “eugenic scientists considered feeblemindedness, and thus undesirable social behaviors, to be hereditary.”46 Cutting off a lineage, though an aggressive overreach of government paternalism, would hypothetically save the welfare department money while also taking steps toward the ultimate goal: A “utopian” society where everyone is White, well-off, and the impacts of the systematic disenfranchisement of Black people (or anyone, really) can never be seen.47 “Sterilization seemed to offer an easy medical solution to complex social problems,” says Schoen. “As concern about consistent poverty and accompanying welfare costs grew, so did the number of eugenic sterilizations performed.”48

This environment in the state led to the sterilization of Debra Blackmon in 1972, a 14-year-old just a few years following Elaine. Her niece, Latoya Adams, shared details regarding the lies told to Debra and her family with NPR: “They were telling my grandparents that the surgery was going to be minimally invasive. They told them it would be a tubal ligation.” Unfortunately, like Elaine Riddick and tens of thousands of other North Carolinian girls, the doctors and social workers were lying. “They wound up doing a full abdominal hysterectomy on a 14 year old.”49 Debra was not treated as a child with a reproductive destiny ahead of her, but as one among many placing a “burden” on the U.S. welfare and medical system. She was adultified, labeled “feebleminded,” and she and her family were lied to. All this was done in the name of the eugenic ideal: a world without poor people, especially if they were Black.

These lies are echoed in cases of forced sterilization across the United States. While North Carolina was enacting its own eugenics program, the federal government began funding sterilization for poor women across the country in the 1960s and ‘70s due to concern about the growing U.S. population.50 This interest resulted in the creation of the Commission on Population Growth and the American Future, which used federally-funded family planning services to promote sterilization to all poor women. And in 1970, Congress passed the Family Planning Services and Population Research Act, providing doctors in state hospitals with reimbursements for sterilization up to $720.51

In addition to Black women like Elaine, this acutely impacted Indigenous women in the United States, who depend on the federally-funded Indian Health Services after centuries of Tribal Nations being betrayed by the U.S. government. Doctors providing sterilizations under the IHS would receive a government subsidy of 90% of the cost of Indigenous women’s sterilizations, whose population was already small.52 Because of the financial incentive, White doctors found any way they could to justify the sterilization of their patients, even if it meant lying about the seriousness or the method of the procedure. This resulted in the sterilization of thousands of Indigenous women, and has left a harrowing impact on their communities for generations.

This policy was also extended to the women of Puerto Rico, whose state hospitals and workplaces incentivized their sterilization at every possible opportunity. As the U.S. government pushed eugenic policy further on the island, pop-up sterilization clinics opened up in factories and other female-dominated workplaces.53 They incentivized how quick, easy, and low-stakes the procedure was by placing it somewhere Puertorriqueñas could access on their lunch break—a mirage quickly broken after they received La Operación, and realized how permanent it really was.54 Doctors, pressured by the United States’ colonial mandates, would offer any lie they needed to to get Puerto Rican women in the door—given that these procedures were subsidized by the U.S. government, there was a financial incentive for them, as well.

This strategy is an imprint of the earlier, North Carolinian choice to deputize social workers to find potential sterilization cases. Offering individual, White employees of the state the opportunity to choose the trajectory of racialized girls and women’s reproductive lives was a dangerous choice, given the amount of eugenic thought and social Darwinism present at the time. Furthermore, the presence of a financial incentive additionally encouraged doctors and social workers to use shame, fear, and flat-out lying to obtain consent for a sterilization. When the subjective metrics of the White gaze are given this kind of power, it is girls like Elaine Riddick, Debra Blackmon, and all the Chicanas and Puertorriqueñas sterilized by the United States who face the consequences.

The Legacy of Forced Sterilization

With the example of Elaine Riddick as a guide, today’s social workers, health care providers, educators, and community members can work to honor the reproductive agency and bodily autonomy of girls and women—of all race and class backgrounds. However, despite Riddick’s work as an adult to draw attention to the truth of forced sterilization and its living legacy in the United States, the same forces which allowed for her trauma remain at play in the United States.

In a unique cultural moment of simultaneous hyper-inclusivity and hyper-exclusivity, hyper-sexuality and nuvo-Puritanism, and increasing economic and racial anxiety as we enter the later stages of capitalism, poor Black girls like Elaine are caught in a complex web of shame and fear. While forced sterilization for disabled people is currently legal in 17 states55—and it is actually illegal in North Carolina56—there is not currently a systematic project of sterilizing poor, Black, Indigenous, Chicana, or Puerto Rican women in the United States. However, these histories remain, haunting our reproductive health care system with myths, stereotypes, and the remnants of the same old shame and fear around sex. But these remnants are not simply specters: they are warnings.

These present-day pieces of this country’s legacy of forced sterilization—particularly the state of North Carolina’s—can be seen in the way the state teaches about sex, sexuality, and reproductive medicine. While today’s training materials for prospective obstetricians and gynecologists still contain plantation and eugenic science,57 modern shame- and fear-based models of sex education contain even more possibility of historical tropes being reproduced, which can then reproduce historical tragedies. In 2025, the state of North Carolina is required to teach sex education, including the bare-bones of pregnancy prevention, sexually-transmitted diseases, and HIV. However, this sex education does not need to be comprehensive, it has a major emphasis on abstinence, there is no mention of consent, and students are taught that “a faithful monogamous heterosexual marriage is the best lifelong means of avoiding STDs.”58 This “education” is based in shame, and designed to instill fear in students so they remain abstinent until entering the fantasy of a monogamous, cisheterosexual relationship, recognized in the eyes of a Protestant Christian God and the County Treasurer.

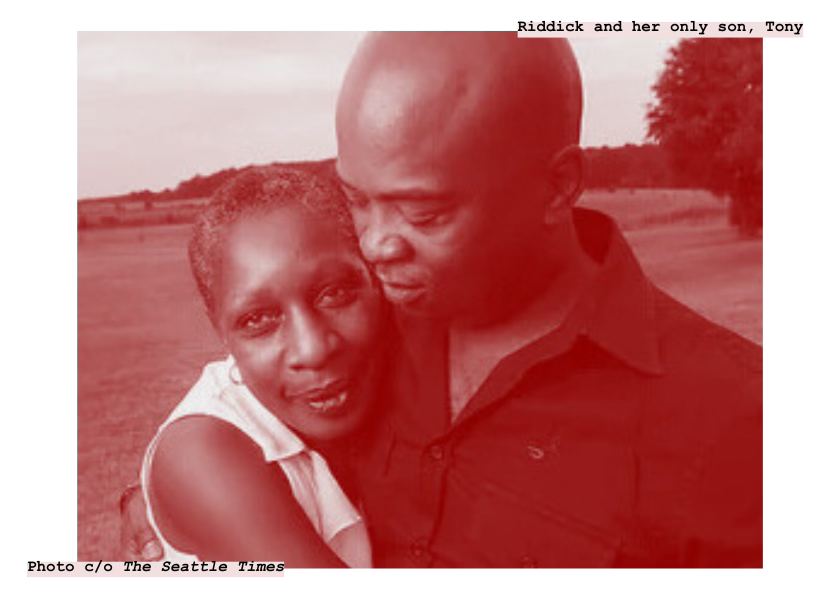

Black girls like Elaine Riddick, to be clear, were not necessarily looking to stray from that path. "When you're a little girl, what do you want? You want to be a mommy,” said Riddick in 2012. “To find out that's been taken away from you is devastating."59 Regardless of her adherence to the norm, Elaine was violated, then sterilized. Her tragic story serves as a solemn reminder of the shifting goalposts of White supremacist projects, and how Black girls and women today cannot fully escape the horrors of medical racism, even when they stick to the “right” path. Even when Black girls and women do everything right, there is a medical, social, even legal system dedicated to upholding White supremacy, not uplifting communities.

Even when these entities use smart marketing or wield public panic, as they did with the “population bomb” or “population explosion” in the ‘60s and ‘70s, these eugenic projects consistently end up the same. They leave bright, young women—like Elaine, like Debra, like Nial, and like all those Black, Indigenous, Chicana, and Puerto Rican women sterilized by the United States—with a reproductive destiny not of their own choosing. They leave poor, racialized women traumatized in mind, body, soul, and lineage.

If the health care and educational systems were to operate under a model of reproductive freedom—or better yet, reproductive justice—instead of a model of shame and fear, young people, students, social workers, health care providers, and educators could have the opportunity to truly deepen their knowledge of the world, themselves, and their communities. By providing people with unbiased, coherent information about their bodies, outside the boundaries of legal- and medicalese, people would be empowered to interact with themselves and with the community in a healthier, more confident way.

This approach is what girls like Elaine Riddick deserved, instead of the legacy she was forced to carry. But her show of resilience, personified in her telling her story at every opportunity, can serve to protect and warn the young Black girls of today, and all women coerced, manipulated, and brutalized by the United States government, social services, and medical system.

CBS. “Sterilization Victim: I Was Butchered.” YouTube, CBS News, 22 June 2011, www.youtube.com/watch?v=MebGHUjs1IE.

Rose, Julie. “N.C. Considers Paying Forced Sterilization Victims.” NPR, NPR. 22 June 2011, www.npr.org/2011/06/22/137347548/n-c-considers-paying-forced-sterilization-victims.

CBS, 2011. “Sterilization Victim: I Was Butchered.” YouTube.

Ibid.

Schoen, Johanna. 2005. Choice & Coercion: Birth Control, Sterilization, and Abortion in Public Health and Welfare. Raleigh: University of North Carolina Press. 76.

Schoen, 2005. Choice & Coercion. 76.

Ibid.

National Women’s Law Center and Autistic Women & Nonbinary Network. “Dignity Denied: Forced Sterilization of Disabled People in the United States.” National Women’s Law Center, 2022. https://nwlc.org/resource/dignity-denied-how-discriminatory-school-discipline-leads-to-school-pushout/

Schoen, 2005. Choice & Coercion. 76.

Ibid.

Schoen, 2005. Choice & Coercion. 75.

Ibid.

Schoen, 2005. Choice & Coercion. 76.

Rose, “N.C. Considers Paying Forced Sterilization Victims.” NPR, 22 June 2011.

Ibid.

CBS, 2011. “Sterilization Victim: I Was Butchered.” YouTube.

Ibid.

Shepherd, Sophia. “The Enemy is the Knife: Native Americans, Medical Genocide, and the Prohibitions of Nonconsensual Sterilizations.” Michigan Journal of Race and Law, 27: 89 (2021). 98.

Schoen, 2005. Choice & Coercion. 109.

Schoen, 2005. Choice & Coercion. 76.

Schoen, 2005. Choice & Coercion. 80.

Spillers, Hortense. "Mama's Baby, Papa's Maybe: An American Grammar Book." Diacritics 17.2 (1987): 65-81.

Schoen, 2005. Choice & Coercion. 76.

Eugenics Board of North Carolina, 1960. “1960 Eugenics Board manual.” Eugenics Board of North Carolina, North Carolina Digital Collections.

Human Betterment League of North Carolina, 1945.“What do you know about sterilization?” Human Betterment League of North Carolina, Incorporated, Digital Public Library of America. https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/eugenics-movement-in-the-united-states/sources/1629

Ana María García, 1982. La Operación. Latin American Film Project (New York, NY: The Cinema Guild), 40 mins.

Library of Congress. “A Latinx Resource Guide: Civil Rights Cases and Events in the United States: 1917: Jones-Shafroth Act.” Research Guides at Library of Congress, guides.loc.gov/latinx-civil-rights/jones-shafroth-act.

Shepherd, 2021.“The Enemy is the Knife.” Michigan Journal of Race and Law, 97.

Ana María García, 1982. La Operación.

CBS, 2011. “Sterilization Victim: I Was Butchered.” YouTube.

Venkataramanan, Meena. “She survived a forced sterilization. Activists fear more could occur post-Roe.” The Washington Post, Washington Post. July 24, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2022/07/24/forced-sterilization-dobbs-roe/

Venkataramanan, “She survived a forced sterilization. Activists fear more could occur post-Roe.” The Washington Post, July 24, 2022.

Rogers, Emme. “The Pervasive Legacy of Medical Racism and Its Role in the Black Maternal Health Crisis.” Institute for Women’s Policy Research, Institute for Women’s Policy Research. April 22, 2024.

Zellars, Rachel. “Black Subjectivity and the Origins of American Gynecology.” Black Perspectives, African American Intellectual History Society. May 31, 2018. https://www.aaihs.org/black-subjectivity-and-the-origins-of-american-gynecology/

Zellars, “Black Subjectivity and the Origins of American Gynecology.” Black Perspectives, 2018.

Ibid.

Ali, Ihotu, MPH, LMT, Erin Wilson, MPH, and Rebecca Dekker, PhD, RN. “Debunking Racist Myths About Pelvic Shapes.” Evidence Based Birth, Evidence Based Birth. https://evidencebasedbirth.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Debunking-Racist-Myths-about-Pelvic-Shapes-Handout.pdf

Ali et. al., “Debunking Racist Myths About Pelvic Shapes.” Evidence Based Birth.

Caldwell WE, Moloy HC. 1933. “Anatomical variations in the female pelvis and their effect in labor with a suggested classification.” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 36:42.

Bradley, James. “The ape insult: a short history of a racist idea.” Find An Expert, University of Melbourne. May 30, 2013. https://findanexpert.unimelb.edu.au/news/3043-the-ape-insult--a-short-history-of-a-racist-idea

Handa, Victoria L., Mark E. Lockhart, Julia R. Fielding, Catherine S. Bradley, Linda Brubaker, Geoffrey W. Cundiff, Wen Ye, and Holly E. Richter. 2008. “Racial differences in pelvic anatomy by magnetic resonance imaging.” Obstetrics and Gynecology, 111: 4. 914-920. https://utsouthwestern.elsevierpure.com/en/publications/racial-differences-in-pelvic-anatomy-by-magnetic-resonance-imagin#:~:text=In%20addition%2C%20among%20women%20who,development%20of%20pelvic%20floor%20disorders.

Dr. Symphony Fletcher, April 3, 2025. “Histories of Abortion & Forced Sterilization.” University of Chicago. Lecture.

CBS, 2011. “Sterilization Victim: I Was Butchered.” YouTube.

Renee Tajima-Peña, 2015. No Más Bebés. Moon Canyon Films and the Independent Television Service (Los Angeles, California: Latino Public Broadcasting). 79 minutes.

Schoen, 2005. Choice & Coercion. 83.

Ibid.

Schoen, 2005. Choice & Coercion. 90.

Rose, “N.C. Considers Paying Forced Sterilization Victims.” NPR, 22 June 2011.

Shepherd, 2021.“The Enemy is the Knife.” Michigan Journal of Race and Law, 95-96.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ana María García, 1982. La Operación.

Ibid.

National Women’s Law Center and Autistic Women & Nonbinary Network, “Dignity Denied: Forced Sterilization of Disabled People in the United States.” 2022. https://nwlc.org/resource/dignity-denied-how-discriminatory-school-discipline-leads-to-school-pushout/

Ibid.

Cunningham F, & Leveno K.J., & Bloom S.L., et al. 2013. Williams Obstetrics, Twenty-Fourth Edition. McGraw Hill.

SIECUS, 2024. “North Carolina’s Sex Education Profile.” North Carolina State Profile, SIECUS: Sex Ed for Social Change. https://siecus.org/stateprofiles/north-carolina-state-profile/

Woods, Carolyn. 2012. “ELAINE RIDDICK, EUGENICS PROJECT SURVIVOR, SPEAKS FOR BLACK HISTORY MONTH.” Forsyth Library, Forsyth County of North Carolina. https://forsythlibrary.org/article.aspx?NewsID=17330

Thank you for highlighting Elaine’s story but even more so discussing the reality of woman of color and poor women who have and continue to be victims of eugenics.

Amazing article. I'm studying to be involved in reproductive justice and advocacy and this just solidified my motivation.