yellowjackets: misty f*cking quigley

embracing The Wilderness, ASD, and the lust in loneliness

ALERT! Below contains serious spoilers for Yellowjackets: Seasons 1, 2, and 3. Catch up on SHOWTIME before joining the team! Buzz Buzz Buzz!

The women of Wiskayok are trying to forget their pasts.

Taissa is running for mayor, supported by her understanding wife and her son. Natalie is going to wellness retreats to quell the memories, and Shauna is having an affair. Their lives—due to a traumatic plane crash, surviving the Canadian wilderness, and yes, cannibalism—splinter into their own distractions and catastrophes. By season three, both timelines show the girls and women circling a drain.

That is, all except for young Misty, who zeroes in on her obsession with the wilderness in ways that are…alarming, to say the least.

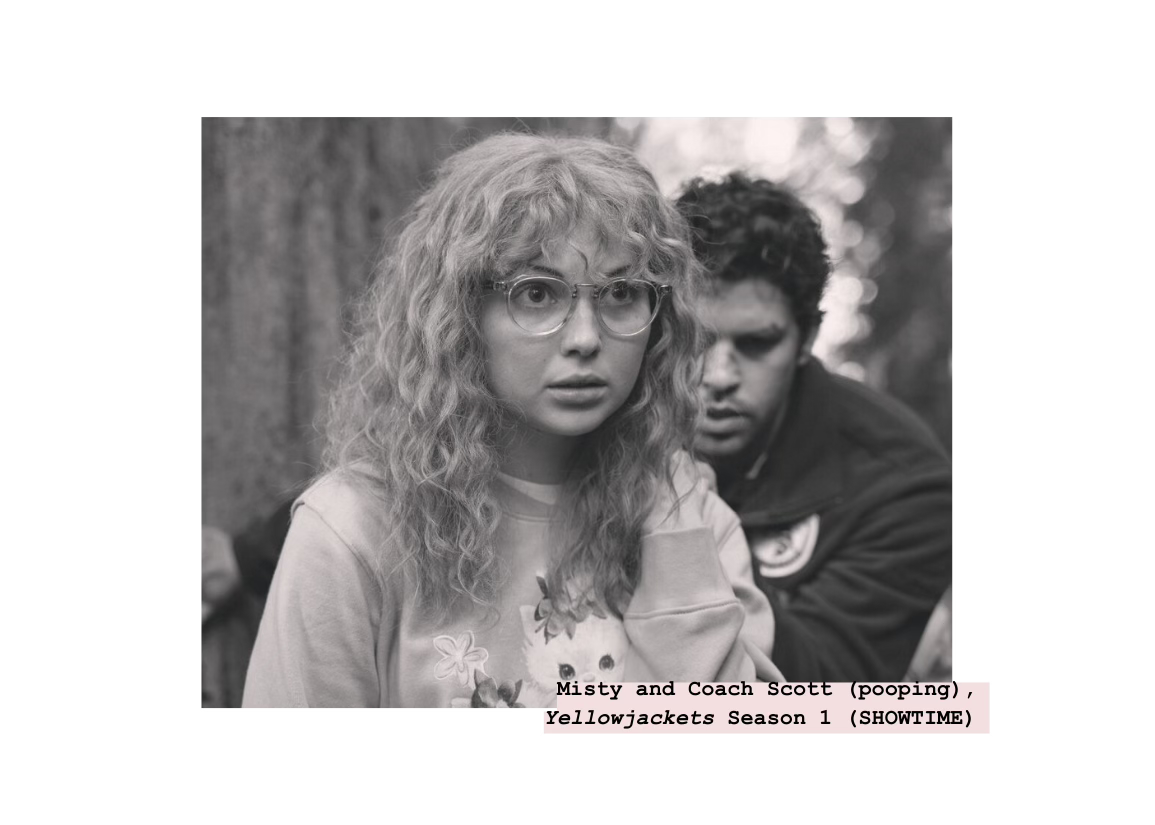

In recent episodes, we watched Misty find her inner Atticus Finch as a play-lawyer for Coach Scott. Misty begrudgingly represents her former, imaginary lover in kangaroo court, but does it with conviction. Intent. Respect. When Coach Scott refers to the forthcoming trial as a sham, Misty reminds him not to speak like that. When the team erupts in an uproar, following the discovery that Natalie has secretly known Coach Scott’s whereabouts for months, it is Misty who calls, wide-eyed, for order. When Natalie—the Judge—is called to the stand, it is Misty who is outraged by this break in their faulty judicial process.

This should come as no surprise to long-time viewers. From her first days in the Wilderness, Misty took to the Canadian woods like Shauna took to a meat slab. Being a vital part of the team’s survival gives Misty a purpose, direction, and power she never had at Wiskayok High, or the broader world of ‘90s New Jersey. While the other girls find chaos in the Wilderness, Misty finds comfort in the sense of order offered by the natural world. You live, or you die. You eat, or you starve. She knows what she’d rather pick, every time.

In the Wilderness, Misty finds her agency—the question is whether she ever leaves it.

Yellowjackets is a favourite portrayal of ours when it comes to unlikeable women, because those “unlikable” characters (who we’re major apologists for, just look at who we’re profiling first!) are portrayed so holistically. Thanks to the parallel timeline structure, the tactful writing, impressive acting, and strategic show direction, the audience is able to do more than watch these women—we come to understand them. Yellowjackets reminds us that, most of the time, unlikeable people are traumatised people, working through hurt and fear with the little care that’s been given to them. While we watch the women spiral in their adult lives, we’re constantly reminded of the source of that spiral. We’re encouraged to imagine the difficulty of reintegration, given the extent of the girls’ experience; after the girls were finally fished out of the wilderness, they were probably bombarded with public attention, followed then by the silence that often comes after with female victims. That can’t be good for traumatised teenage girls, I fear!

In the present timeline, most of the women appear haunted by the plane crash and ensuing events of 25 years ago. This, of course, results in very useless methods of repression that do more harm than good in the long run. Misty, however, does not repress anything. In the Season 2 finale, she lovingly refers to their time in the Wilderness as “that first summer,” not expecting her teammates to quickly snap at her—Van describes it as “our time in fucking oblivion.” In Season 3 Episode 3, Misty claims that she’s been to a sleepover before, as “What was our time in the Wilderness but one big sleepover?”

While juvenile in her representations, Misty is also unashamed. She is the only one unafraid to romanticise their time in the Wilderness, signifying an acceptance of that time as a vital piece of her development—not a bug, but a feature. Like Natalie, Misty believes her time in the Wilderness to be more purposeful than her life outside of it. But unlike Nat, Misty can’t help her desire to go back, even if it means sacrificing their chances of normalcy —see: the damn black box—for her saviour complex.

It does, in fact, sound insane. But there is always a reason.

Let’s review Misty’s life before the Wilderness, shall we?

Misty is set up as our Piggy, if we’re still following the Lord of Flies parallels Jade discussed in the first article in this series. She has horn-rimmed glasses and freckles. She sits on the sidelines excitedly while the Yellowjackets practice, play, and rally. She is ridiculed, teased, and bullied by her classmates, as evidenced by a prank call in the pilot episode, where Misty is accused of “not being hot enough to get someone to do anal with.” (She responds, poetically, with “Opinion is wilderness between knowledge and ignorance.”) Despite all this, she believes herself to be a Yellowjacket—she shouts “Buzz Buzz Buzz!” loudest, after all. But her lack of invites to parties or extracurricular hang-outs with the team demonstrate her to be quite the opposite.

The day before the plane crash—while the other Yellowjackets are getting fingered, fucked, and meeting Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds together—Misty watches a lone rat drown in a pool. We’re not even sure if it’s her pool! All we know is that she is alone, and she watches it die, expressionless. Our initial images of Misty are equally as ruthless as they are pathetic. The former comes to the fore the moment that burning plane crashes down in the Canadian Wilderness.

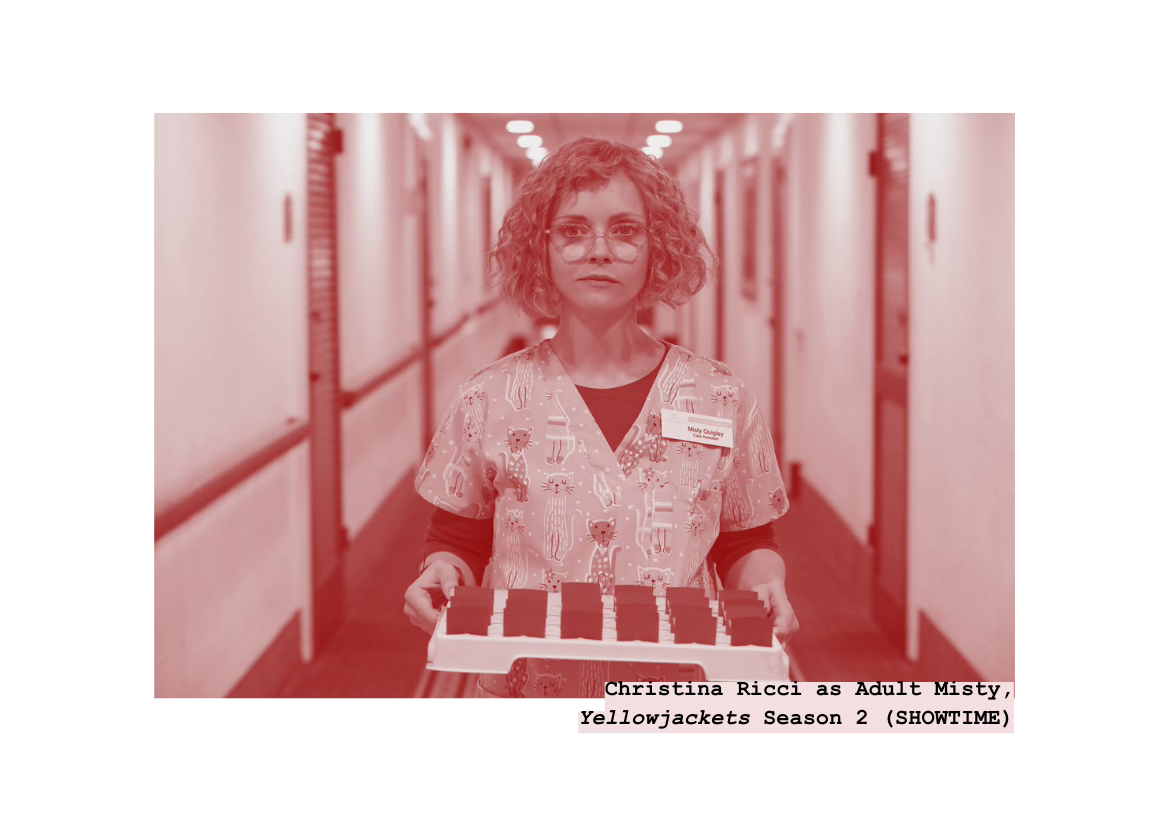

If we revisit the events following the crash, the person that held the most capability—despite being shunned and ostracised in her New Jersey life—was Misty. She amputates Coach Scott’s leg while the other girls stand around and watch. She provides help to injured people around the crash site, like the abandoned and singed Van. Misty enthusiastically puts herself to good use, because in the Wilderness she is useful. This continues into the present-day timeline, as well; where Shauna and the other women berate her for her socially inappropriate behaviour, Misty ends up being the quickest on her feet when they inevitably do something stupid.

For a person with little to no social skills, Misty finds herself, for the first time, in a position where she can be helpful—where others need her help. She glowingly eavesdrops on the other girls, who admit (only in secrecy) that they’d be screwed if Misty weren’t there. But, of course, her Wilderness chops are explained away by her being a “freak,” as Misty has always been. Her “freak” flag only brings her power as long as she’s in the Wilderness. So what is she to do when there’s an opportunity for them to leave? Go back home, where she serves no purpose?

No. Misty must destroy the flight recorder. She must stay useful, and to stay useful, she must stay in the Wilderness.

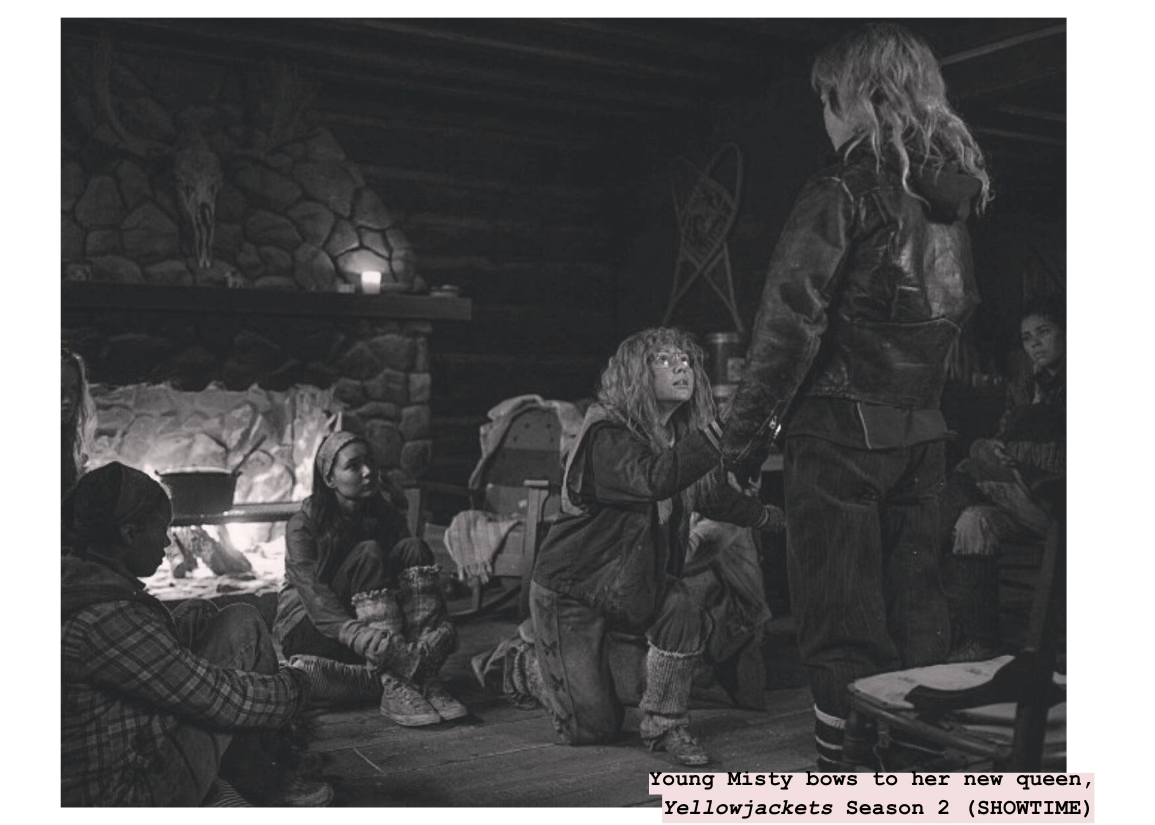

In every scene afterwards, Misty is fighting to keep her shaky status as the unlikely hero of the crash. She fights to keep her secret while slowly proving herself to everyone else. She heals wounds. She takes out the shit bucket. She delivers Shauna’s still-born child, soaked in a mix of the team’s blood, sweat, and tears. She holds Natalie back from saving Javi when he breaks through the frozen lake, deciding on behalf of the group who would be more valuable to keep, and who would be better to eat. After Lottie is beaten to a pulp by Shauna, it’s only Misty who’s allowed to speak to her—and it’s Misty who reminds Lottie of her responsibility, as makeshift leader, to keep up the spirits of the group. Like it or not, Misty is a quiet leader in the Wilderness, despite standing on (literal) thin ice. When it comes down to it, Misty always gets her way.

As repeatedly suggested in feminist TV milieu, Yellowjackets uses the Wilderness to greater magnify the very real stakes of girlhood. (Cue jeering from the peanut gallery.) The Wilderness makes every second life or death, parallel to the experience of living inside a teenage girl’s mind. However, the intrigue of Yellowjackets is that we dissect the interpersonal relationships these girls form with each other—just as teenage girls are wired to do—whilst trying to literally stay alive. This accelerates the consequences of the girls’ actions, seemingly matching them up with the percieved stakes of teenage girldom.

Take Shauna: Sleep with your bestie’s boyfriend? Not only are you now pregnant, but you’re in the Wilderness, with no medical help, no (non-human) food, and nothing but Akilah, her dead mouse pet, and Misty Fucking Quigley to help deliver the baby. Get into a stupid fight? Your bestie died in her sleep from hypothermia—and yes, it’s unequivocally your fault! While the costs of teenage social relations may feel extremely steep, it’s Yellowjackets which actually takes us to that place of catastrophisation—if I don’t maintain close bonds with the girls around me, will I die? (If we look to Snackie as an example, then unfortunately, yes.)

So who can blame Misty when she is also just trying to stay alive? Her methods differ, clearly, but where is the guide book for teenage girls stranded in The Wilderness? What is Misty missing—and is it what helps her to stay alive?

Let’s talk ‘tizzy, shall we? One of the favourite fan theories—and one Ennie wholeheartedly has convinced Jade of—is that Misty is actually on the Autism spectrum. This characterisation of Misty has been appreciated by watchers on the spectrum, who saw themselves in our favourite little freak. The show never explicitly diagnoses her, but watchers recognise her socially awkward behaviours and her obsession with close association to leaders like Natalie and Lottie as signs of being on the spectrum.

Despite the slowly changing stigmas around autism in women and girls, there are situations where some go undiagnosed for their entire lives. Differences in gender socialisation result in differences in how Autism presents: While boys are stereotyped as hyperactive, aggressive, or tunnel-visioned on a special interest, girls may engage in mimicry, social isolation, or intense friendships, which are often taken more as individual quirks than the tell-tale signs of Autism spectrum in boys, which result more often in medical and psychiatric intervention.1 According to Donna Williams, "...right from the start, from the time someone came up with the word ‘autism’, the condition has been judged from the outside, by its appearances, and not from the inside according to how it is experienced."2

The American between us is happy to go out on a limb here: There’s no way that ‘90s New Jersey would have the attentiveness toward girls and women on the spectrum that Misty likely needed. Until very recently, the poster child for Autism, ADHD, and really any flavor of neurodivergency was young, white, “hyperactive” boys. This categorisation was done less to support the children being labeled, and more to placate frustrated teachers and parents; providing a government-approved dose of methamphetamine before kids’ frontal lobes have a chance became the U.S. medical system’s MO. Today, according to the National Autistic Society, “More women and girls than ever before are discovering that they are autistic. Many had been missed or misdiagnosed due to outdated stereotypes about autism.”3

In Yellowjackets, Misty expresses quite a few of these signs. The way she talks, the way she acts, and her attempts at masking as a neurotypical person—despite her obvious differences with all the others—ring true to the experience of girls on the Autism spectrum. We watch her deal with past and present traumas—almost entirely—alone. When she feels afraid or frustrated with herself, she doesn’t go to the girls for help. She collects herself in a corner or in a bathroom, tearfully arguing with her own reflection: “You always do this! You always do this!” When Walter (overbearingly) dedicates himself to supporting Misty through Natalie’s death, reminding her consistently of how he is the only one who cares about her, she unceremoniously removes him from her life. She won’t tolerate his questioning of the Yellowjackets’ bond to each other. She won’t allow him to lift the wool from her eyes. Misty doesn’t seem to trust anyone but herself—well, or the Wilderness.

Furthermore, Misty cannot find true affirmation in her teammates—they ridicule her even when they need her. But Misty finds an early kinship among the trees and the wind; here, she is safe, surrounded by animals and spirits telling her she belongs. Misty’s social gaucheness springs from just that: a (potentially) neurodivergent teenage girl’s desire to belong. She cares deeply—perhaps in ways most people find off-putting—and wants to be cared for in the same way. But as the story progresses and we watch Yellowjacket after Yellowjacket bite the dust, Misty’s dedication to the Wilderness—regardless of the depravity of eating your friends—seems to increasingly other her from the team, past and present. Despite others having done arguably worse things, Misty is incapable of hiding what she feels; instead of helping her, the Yellowjackets—even into adulthood—end up using her.

Yellowjackets works best when interrogating the ‘Othered’ experiences of girlhood against the backdrop of the Canadian Wilderness. Some of these teenagers (like Misty, Shauna, Natalie, and Van) seem to be an afterthought in their own lives back home, but transform into pagan ritualists, skilled deer hunters, and respected butchers in their Wilderness. Misty’s unpredictable behaviour is a consequence of negligent parenting, and of a society that fails people on the margins—but out here, her volatility keeps her alive. The question is: Does Misty know that?

Is Misty, the outcast teenager with underdeveloped social cues, aware that she might be a bad person?

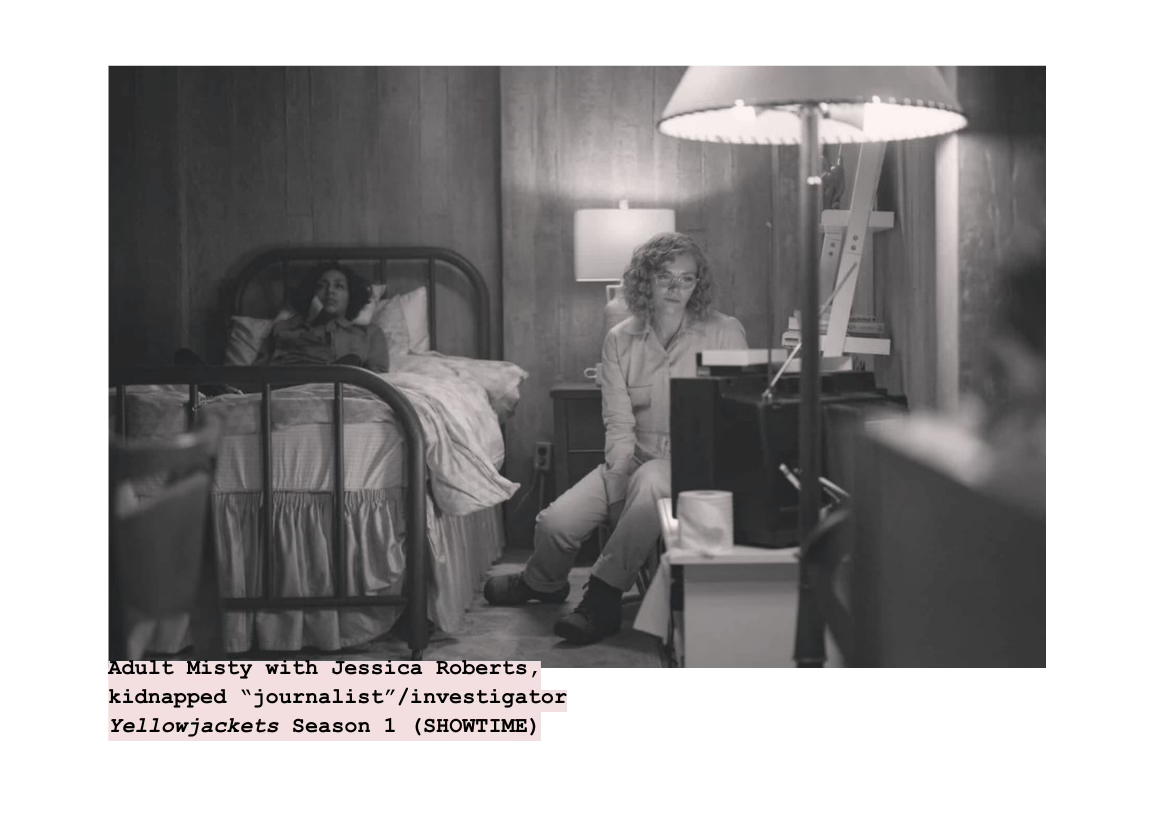

Now, this isn’t a diatribe about how Misty’s the best and most likeable character—even if she is the most fascinating. We can’t absolve her of her wrongdoings simply because of her undiagnosed autism. Throughout both timelines, Misty does some deplorable things, using her own pathetic nature and air of harmlessness to fool her victims into doing what she wants.

Misty Quigley has:

killed and attempted to kill more than one person, in and out of the Wilderness, both inadvertently and purposefully (chicest murder weapon award goes to the fentanyl cigarette);

kidnapped and attempted to kidnap more than one person;

openly emotionally manipulated a man she was on a date with to get him to sleep with her after realising he doesn’t like her;

weaponised her saviour complex to get closer to Coach Scott as a recent amputee, despite his disdain for and fear of her

used Walter, her fellow Citizen Detective and (briefly) live-in boyfriend who seems to genuinely love her, and berates him regularly as a friendless freak. (Pot, kettle.)

What murda??? Unfortunately, there are too many to pick from. Our girl really is a freak.

So whose fault is this? By some arguments, Misty doesn’t actually know what she’s doing. She might be an adult, but undiagnosed autism simmering with layers of trauma does not bode well for the way she handles things. And if we’re subscribing to the idea that the girls’ time in the Wilderness is all a group hallucination—brought on by the combo of shrooms, starvation, and that trippy cave—then Misty’s noggin might be the most far gone. On the other hand, Misty is fucking creepy, and does creepy shit! And she has masked her autism for long enough that she should know it’s wrong to kidnap people. Where she hopes beyond hope for experiences of belonging and power—manifesting in her pursuing a career in elderly care, one rife with opportunities for abuse—she often finds herself in situations where she is trying to wrestle these things (in addition to their literal lives) away from the people around her. However, is it possible that she really doesn’t understand the impact she has?

The Double Empathy Problem—when neurotypical people struggle to understand and empathise with neurodivergent people and vice versa—might offer some clarity here. Misty seems to have a markedly different lived experience from her fellow Yellowjackets, despite the fact that so many of them share the status of being “Othered” in some way. Is it possible that the experience of Misty and, say, Crystal would be so different that Misty wouldn’t recognise her threat to kill Crystal as serious? Serious enough where Crystal was scared into slipping to her death? Maybe. But with Misty, regardless of reasoning, the consensus states: She needs mental help. Can someone please chopper our girl out of there?

What we can assume of Misty comes from our own understanding. Whether we know it or not, we all have, to some degree, a Double Empathy Problem. If you scour the first couple search results on Reddit of ‘Misty in Yellowjackets’ the word 'psychopath' will come up about a million times. It’s quite easy, at first glance, to assume that’s who she is. Of all the girls, she has the least backstory—we only know a dead rat. But is it also possible to assume that, because it’s Misty, the showrunners are representing the lack of care in Misty’s life? Like a large percentage of autistic women and girls, perhaps Misty has never been given the full breadth of care she needs—her relative invisibility before the Wilderness could prove as much. With Misty, Yellowjackets’ showrunners drive home what seems to be their focal point: It will always be harder for women to be seen, especially when those women are bad people.

Ennie thinks about this often—how different a person’s adult life would be if they were better taken care of as children. On face value, we can berate and diagnose people with the worst identities imaginable—murderer, cannibal, freak, sadist. But who were they before that? Underneath that?

This isn’t us telling you to empathise to rapists or serial killers—or even cannibals. Just empathise, for a second, with our Misty.

Perhaps, if the crash had never happened, Misty could've gotten help. She could have trained a little more at her soccer skills on the side, and gotten bumped up from ball girl to team member. Maybe her invisible parents would materialise, scoop the drowning rat from the pool, and all load into the family VW bus to get Misty a ‘tizzy test—hunky dory! Perhaps Misty could have built a life—a real life, in New Jersey—without the nineteen months of life-altering trauma.

But we—the girls, sorry—did crash. Instead, Misty did live in The Wilderness—in fact, she finds that she’s wanted there. She’s important. She’s not a coach’s assistant, or the weirdo that people prank call and avoid.

She’s Misty Fucking Quigley, and she’s lethal as fuck.

Hello from the omniscient beyond! Keep scrolling or purchase a trial subscription to JADE FAX to listen to an audio conversation between the authors! Jade interviews UK-based

on all things Yellowjackets, her upcoming writing projects, and the best way to eat your bestie (cured, possibly).Subscribe to and follow her work today!

Donna Williams, Autism: An Inside-Out Approach. 1996.

Ibid.

Ahh, this all makes so much sense. I've often wondered why so many fans find it far easier to have empathy for Shauna versus Misty, and why they frequently bring up Shauna's lack of family details while again glossing over the fact that we know even less about Misty's family. In passing, I've thought to myself how I, perhaps unfortunately, relate the most to Misty, despite finding so many of her actions deplorable. I've also thought that she's probably on the spectrum, like myself, but I've never really connected the dots as you've done here. Which seems frankly absurd since I was diagnosed late in adulthood. I really enjoyed this take. It helps me realize how much I recognize Misty's intensity, desire to matter, and propensity for obsessive daydreaming. I've grown and matured greatly, and I'm not on her level of traumatized, nor am I ruthless... but I do feel strangely seen by her character, and a bit wounded (as in, it hits too close to home) when other viewers find something to like about every other girl EXCEPT her. Thanks for this! It gives me lots to ponder.

I’ve never watched the show, but your writing drew me in. I’m autistic, and as I was reading, before you mentioned autism, I kept muttering “this character they’re describing sounds autistic.” So, yeah. 🌝 I don’t think I’m watch the show, but I really enjoyed this. Thanks!