your fave is selling a pedophilic fantasy

sabrina carpenter doesn't mind being your "sexy baby"

I’m going to allow you to read the title of this essay, take a deep breath, then join me in the discourse.1

Ardent defenders of white, blonde popstars: You can do this.

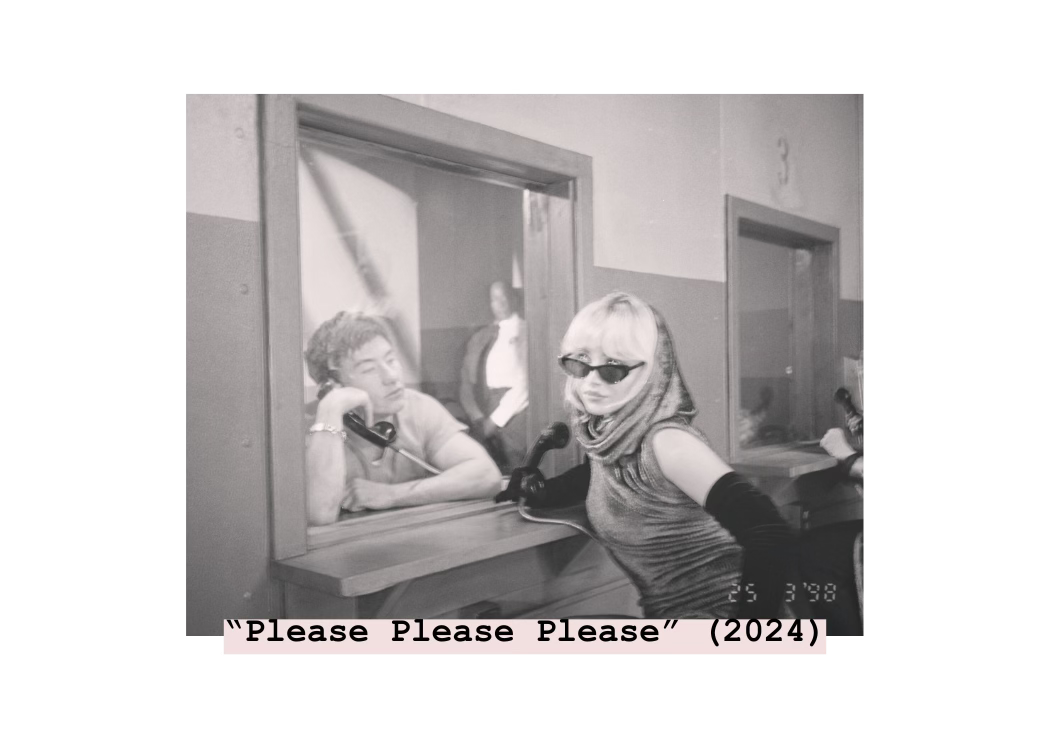

Let me start here: I am a dedicated fan of pop music, especially that written by women. I would describe myself as a casual consumer-to-fan of Sabrina Carpenter. My summer was spent with the constant backdrop of “Me Espresso.” A friend and I dramatically scream-sang the lyrics to “Please, Please, Please” to our boyfriends in the middle of my post-grad dive bar. “Feather” is a vital feature on my poolside playlist. Following the commercial release of her newest album, Short n’ Sweet, Sabrina—can I call her Sabrina?—and performers of her class are ushering in a Gen-Z-girl-pop renaissance: one chock-full with themes of girlhood, glitz, and lots and lots of yearning.

Considering we’re fresh off the “Year of the Girl” in 2023, Sabrina’s bubblegummy, crooning record fits neatly into the culture. If the constant churn of near-identical Substack essays about girlhood—written, of course, by twentysomething women—signal anything larger about women consumers, it’s that we’re, well, regressing.

By my most generous analyses, years of lockdown and collective trauma from the COVID-19 pandemic have women my age clawing back our precious youth. We need the coddling spirit of Barbie (2023) in our movie theaters, the tangible comfort of Sonny Angels in our tiny purses, and the abstract end-goal of a good crush to keep us afloat. We want a teenhood, again: Short n’ Sweet offers a short-term trip back to that mentality.

Tongue-in-cheek from its title to its final notes, Short n’ Sweet doesn’t take itself too seriously. Sabrina makes the record her world: She reinvents grammar, plays with innuendos and double-entendres, and hints at the superstar suitors lying in her wait. For lack of a better word, the album is hot: assumedly the perfect TikTok backtrack for the summer’s It Girls (or perhaps they’re called "Brats” now).

Quinn Moreland articulated it best for Pitchfork:

"In a pop landscape recently plagued by self-seriousness and a tiresome obsession with authenticity, Short n’ Sweet is a refreshing glass of escapism.”2

By my read, Short n’ Sweet is a soft girl’s album; a post-lockdown return to simple music about boys—not boys who abuse, not boys who manipulate, rape, and lie, but boys who are just inherently stupid. She begs Barry Keoghan to behave in the same tone we’ve all used for a shitty boyfriend, or a dog. It’s assumed that they don’t know better—they’re barely house trained—and we girls can laugh along as we collaboratively teach full-grown men how to act. Short n’ Sweet has a politic ending at “girls rule, boys drool;” this simple message and expert pop production has kept the album at Billboard’s #1 for two weeks in a row.

Here’s where Sabrina and my politic diverge.

As I’ve written previously, I see the character of the “soft girl”—particularly when donned by white women—as a first step on a girls-only alt-right pipeline. The originators of this term, Gen Z Nigerian women, had anti-colonial aims and radical rest in mind when creating the “soft girl” Internet persona. Then, white Americans quickly readapted the trend to align with the Christian Pastoral: home-making, Pilates arms, you know the rest. The white trend toward tradwifery—that, yes, ensured the election of a demagogue—replaced the true intention of the Nigerian movement with Puritan gender roles.3 Again.

White American “soft girls” give me pause. For a demographic of women which, historically, have not raised their own children, have not performed the majority of domestic labor, and have been kept out of the public sphere, it’s logical to meet the overwhelm of modern, feminist life with a desire for return. The boredom and plight of their ancestors has been rebranded into a life of leisure; of paid-for pilates, almond Gel X nails, and endless highlight touch-ups. A life of tortured silence now appears peaceful in contrast to the financial, social, political, and emotional struggle of being a working woman in 2024—a double-bind working-class and BIPOC women have been navigating for centuries.

To achieve this false sense of stability, white women have two choices; find a man willing to time-travel, or do it yourself. And in modern dating, where 50/50 bill splits are commonplace, it’s more likely that “soft girls” will be solo-traveling to their own simpler time: Childhood.

Stay with me, here. The impact of the “Year of the Girl” couldn’t end at media and aesthetics—we both know that. 2023, while a celebration of girlhood, also brought with it the return of heroine-chic, the normalization of cosmetic injectables, the buccal fat removal craze, and an obsession with luxury beauty rearing its head in Gen Alpha. We’re swapping facial moisturizer—and in the worst of cases, the numbers on our scales—with literal 14-year-olds. Youth and innocence, especially post-lockdown, provide adult women social status while endangering the youth we emulate. The line between “girl” and “woman” is being blurred, and it’s women, not girls, who benefit from the exchange.

In fact, it’s also Sabrina.

“He pins you down on the carpet

Makes paintings with his tongue”

“Move it up, down, left, right, oh

Switch it up like Nintendo”

“Come right on me, I mean camaraderie”

“And I bet we'd both arrive at the same time

And I bet the thermostat's set at six-nine”

“Hold me and explore me

I'm so fuckin' horny”

The lyrics above are unquestionably adult: they should be, they’re performed by a 25-year-old. The sexual innuendos and comedic references to female desire are part of what sets Sabrina apart from her peers in the pop scene; while stars her senior have been taught to shy away from explicit content, Sabrina makes talking about sex fun!

From her lyrics on Short n’ Sweet to her infamous “Nonsense” outros, which made their rounds on TikTok throughout her 2022-2023 Emails I Can’t Send Tour and her stint opening for the Eras Tour this year, Sabrina consistently uses sex in her lyricism. While these outros4 have always been dirty, they’ve slowly become more explicit:

“This crowd is giving me all the endorphins/ I wish someone would rearrange my organs/ Philly is the city I was born in!” (October 2022)

“I've got a dirty mind but I am so pure/ Call me Dora, his body I explore/ Fort Lauderdale, you're kicking off the whole tour!” (March 2023)

“Turn that dick to stone, call me Medusa/ Choking on him need Heimlich maneuver/ Sorry I don't date lollapalooz-ers” (August 2023)

“D-I-C-K I am good at spelling/ Tastes so good, I need a second helping/ Aren’t you glad I know how to say Melbourne?” (February 2024)

“Told that boy to sit me down on all fours/ I told that boy go faster, now I’m all sore/ You hit a little different here, Singapore!” (March 2024)

“BBC said I should keep it PG/ BBC I wish I had it in me/ There's a double meaning if you dig deep” (May 2024)

As a Creative Writing student, I'd love to have this woman in my poetry class. As a marketing professional, the slow build and consistent fan return on these outros are a dream for any social media manager. The crudeness of the “Nonsense” outros—what is often new fans’ introduction to Sabrina—is smart music marketing. Sex sells, especially when it’s auctioned off by a beautiful, witty, white woman. There’s also something to say about a young woman explicitly narrating her own sexuality on a public stage—something unavailable to women like her just decades ago.

Here’s the rub: While her content is maturing, Sabrina Carpenter’s packaging is regressing. Her music is made for women, but her branding intentionally communicates a particular version of Girl. Unfortunately, I’m not talking about Substack-essay-girlhood-type emotional regression; the Sabrina Carpenter machine is using a ‘90s-era, hyper-sexualized girlhood as the core aesthetic for an adult singer. And, intentional or not, this branding decision offers audiences the choice of pedophilic fantasy. Knowing American culture, by and large, they will take it.

The above is the penultimate photo in Sabrina’s latest feature for W Magazine,5 a piece including details on her Disney career, the writing process for “Espresso,” and a fashion shoot heavily inspired by ‘50s and ‘60s aesthetics. The Lolita (1997) reference was striking, especially considering the obvious inspiration wasn’t mentioned at all in copy. W Magazine and the Sabrina Carpenter machine cleanly folded Nabokov’s controversial story— about an adult man’s obsession with a 12-year-old girl—into a feature about an adult woman’s child stardom.

This reference is political, and not for any analysis on pedophilic culture. Without reference to or condemnation of its source material, this doesn’t challenge equivocations of a small-statured, former child star to an actual child. In fact, it reads more like an invitation.

Let’s go back to the “Nonsense” outros. The following were performed in the international leg of the Eras Tour this year. Despite public opinion on Taylor Swift’s fanbase, only 5% of Eras Tour attendees were under the age of 18, meaning Sabrina was mostly performing to an audience of her peers—or older. Here’s where things get interesting:

“I’m full grown but I look like a niña/ Come put something big in my casita/ Mexico, I think you are bonita!” (February 2024)

“Gardens by the Bay, I wanna go there / Then, I’ll take you somewhere that has no hair / Singapore you’re so perfect, it’s no fair!” (March 2024)

I’ll allow you to digest, here.

These two particular outros left a nasty taste in my mouth. Not only does Sabrina fall into the trope of “Tiny Sexy Girl”— with a side of “Born Yesterday Sexy”—she is explicitly comparing herself to a pre-pubescent child. She looks like a young girl, her pussy is bald, and she wants you to fuck her. She isn’t sharing this only because it’s funny; for some audiences, these qualities grant her favor and capital.

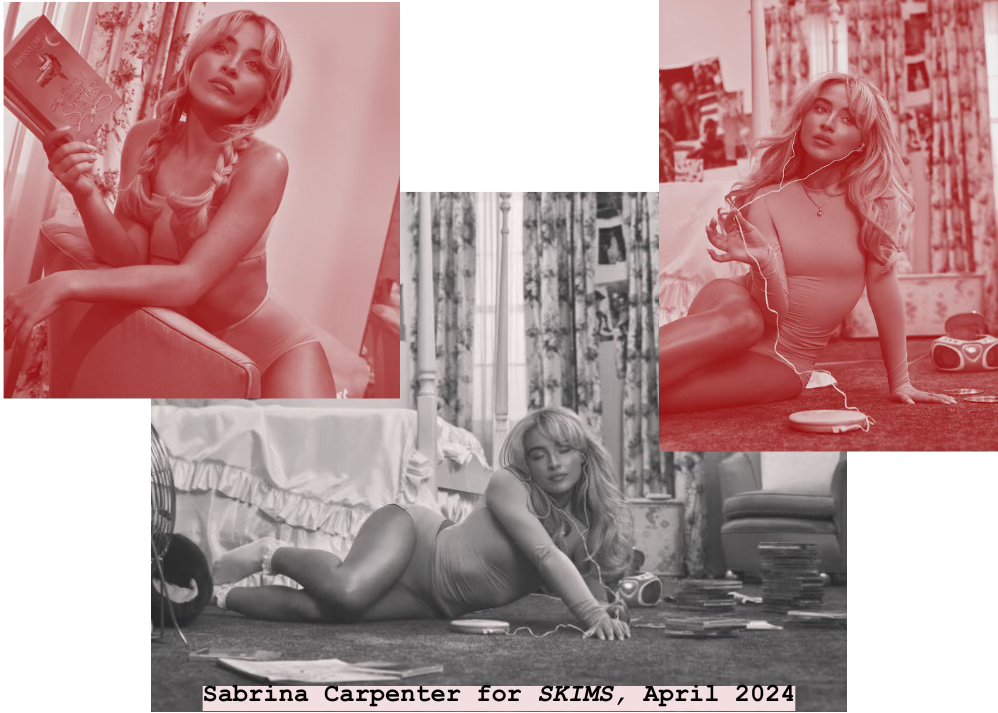

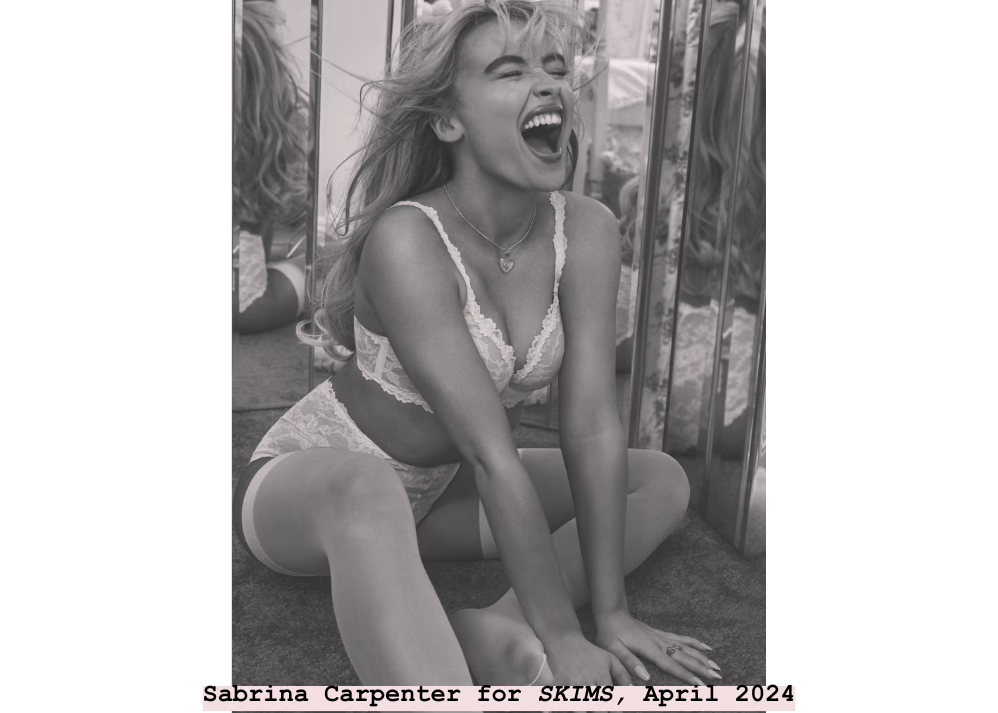

Speaking of capital, Sabrina’s pop-girl status also granted her a Skims campaign this past spring, earning her the same Kardashian endorsement as Charli XCX, Lana Del Rey, Ice Spice, and PinkPantheress.

According to Carolyn Twersky of W Magazine:6

“Getting a Skims campaign is the modern-day equivalent of earning a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.”

While this take might be a tad exaggerated for my taste, Sabrina’s Skims campaign solidified her as one of the culture’s new sex symbols. The rub here is what Sabrina, her team, and Skims chose to do with this newest platform. While Skims has branched out from their nude bodysuit beginnings—now offering camo lingerie, heart-printed baby PJs, even men’s intimates—Sabrina’s campaign felt like a stark departure from their usual MO.

Skims, regardless of your feelings about Kimberly, is a brand built by adult women, for adult women. Modern shapewear—hosiery, spandex, and leotards—remains highly influenced by the working women of the ‘80s and ‘90s, who donned their skin-tight shorts after a long day of workplace sexism, and worked it out to a Jane Fonda cassette. Skims is selling to their modern-day equivalents: their customer base is overwhelmingly Millennial, with 36.24% of website traffic driven by 25-34 year olds, followed closely by 35-44 year olds at 17.94%.

The selection of Sabrina as Skims’ spring muse, according to Kardashian herself, is due to “an ‘It’ factor that really resonates with the next generation.” The target audience for this campaign is Gen Z, made all the more obvious by coquette details like lacy babydolls, vintage-inspired boy shorts, and rosette accents. The pieces themselves, while trending younger than Skims’ usual, don’t ring too many alarm bells. It’s the staging where the fantasy continues:

“Her campaign, shot by photographer Jack Bridgeland, fits perfectly into the nostalgia-fueled, high-feminine aesthetic Carpenter has cultivated over the past few years. ‘I felt like I was a young girl again, playing in my bedroom,’ the singer says of the cinematic set…”

The “nineties nostalgia” the campaign boasts—using, of course, a ‘99 baby as its muse—instead translates to a particular, late ‘90s-early ‘2000s childhood. The PrettyPink CD Radio Boombox, the Sony Walkman (attached, of course, to Apple earphones), the celebrity posters, the (apparently, fake) novel in her hand, whose cover is straight out of 2004? The scene is more specific than “nostalgia”: by Sabrina’s own admission, it’s a young girl’s bedroom.

Juxtaposition is key in editorial fashion, and shock-factor, as Sabrina purports to enjoy, can only add to a celebrity marketing campaign. Seeing a small woman, in a childhood bedroom, decked out in full lingerie brings up all sorts of cultural touch points: American Beauty, Cruel Intentions, The Virgin Suicides, and yes, Lolita. The Skims and Sabrina Carpenter machines are selling our own obsession with youth sexuality back to us, and telling us it’s empowering—in fact, it’s just “feminine”!

See below two quotes from Sabrina on her Skims experience:

“I loved the femininity of the whole creative.”

“It is precious to see women feel like women, and in a way that feels very unapologetically feminine, and I think [the Lana and Ice Spice] campaigns did that really well.”

Allow me the chance to tell two personal stories here.

There’s a woman I’ve known my entire life who, in the last eight years, has clearly gone off the alt-right deep end. I watched through the screen of my phone as the fashion lover, Francophile, and unapologetically dramatic girl I looked up to as a child get engaged at the Trump White House Christmas Party, become a Fox News correspondent, and hear whispers of her outspoken transphobia. She introduced herself to a friend of mine as “porcelain-American,” and in the years following the Capitol Insurrection, her and her husband have never missed a Republican National Convention. Her Instagram bio reads, “Christian, wife, unapologetically feminine.”

In the final year of my Bachelor’s degree—a period of acute depression and stress-induced cystic acne—I held focus groups to research my honors thesis in Women’s, Gender, & Sexuality Studies. I aimed to study how feminists felt about cis-men’s presence in the movement, a Herculean task requiring the near-constant academic backup of bell hooks. One quote, shared by a fellow campus organizer in 2019, still echoes in my head sometimes:

“I think that masculinity in these movements can be really threatening. I genuinely don’t support masculine identities within the feminist movement, because I view so much of the feminist movement as promoting femininity. If you’re someone who identifies as masculine, and you’re masculine presenting, I don’t think you can really, genuinely be involved in the movement if you don’t have those types of experiences.7

These two individuals, to this day, exist on opposite ends of the political spectrum. But they both felt an inherent defensiveness toward the amorphous “femininity"—it is discussed like something endangered, constantly at risk of tainting. (And, yes, they both are exactly what you’re thinking.)

Sabrina—in addition to these two women, and plenty others—worships at the altar of the divine feminine. On one hand, this could promote an empowering, nurturing, intuitive spirit, which supposedly exists within all women. But more realistically, the type of femininity Sabrina, Kim, and Rolling Stone are talking about is one that looks more like her—it’s highly manicured, it’s bubblegum pink, and it’s waif-thin white.

Western “femininity” has been synonymous with whiteness since European colonizers first reached Africa in the 15th century. Willfully ignoring African understandings of gender, sexuality, and society, Portuguese, French, British, and Spanish colonizers sent lewd pamphlets home, depicting exaggerated tales of African sexuality.

According to researcher Caren M. Holmes of the College of Wooster:

“Prior to the British journey to the New World, epic tales of imperialist travelers probed the minds of Europeans regarding the nature of African people. African men were said to have gigantic penises, and it was rumored that African women engaged in sex with apes (McLinktok, 2001). These tales likely reflected the subconscious fears and Freudian sexual confusion of Europeans. However, these dramatized stories were interpreted as factual, and they informed some of the first European perceptions of African people… The perception of black people as hyper-sexualized and uncivilized paved the road for the dehumanization and sexual exploitation imposed upon black men and women brought to the New World.”8

Often containing caricatured drawings of African women’s naked bodies, these pamphlets and stories stoked both power and envy in European women. Power in that their physical bodies could protect them: not only from religious damnation, but from the physical work of chattel slavery. Being white, clothed, small, and relatively weak ensured safety for European women compared to their African counterparts. But envy pervaded, still: just as their husbands, brothers, fathers, and friends talked of the land they were pillaging in feminine terms, they recognized the sense of eroticism colonizers felt toward the African women they documented. More from Holmes:

“The feminization and sexualization of the European imperialist narrative encouraged the sexual exploitation of black women who were perceived as byproducts of manifest destiny.”

And this colonial-era thought persists today. According to the Black Future Fund:

“Historically, in the Western imagination, Black women have been either masculinized beasts of burden, desexualized mammys, or hypersexualized jezebels. These seemingly contradictory stereotypes work together in denying and perverting the humanity of Black women, and seek to cast Black women as perpetual others whose value lies in their labor or sexual availability.”9

The anti-Blackness and anti-Indigeneity within Western definitions of femininity haven’t gone away. Aside from the deep-running trans- and homophobia in American culture, much of the current conversation around women’s sports has been dominated by Western gender essentialism. I think of Algerian Imane Khalif, South African Caster Semenya, Namibians Christine Mboma and Beatrice Masilingi; all Olympians from the African continent whose womanhood was questioned…after beating white competitors.

I actually wrote about this a few years back:

“While the governing bodies of elite sports expect Black women to turn out viewership and funnel money into sports, they remain the descendants of the same colonizers who saw Black women’s bodies as inherently “other.” They took that mentality of fear and control and ran with it for generations; the harm caused to Black women and communities is far from ancient history.”10

Women of color are masculinized by white definitions of femininity, which can range in consequence in a gender-obsessed society. “Femininity" is a tricky tight rope—and it can be revoked just as quickly as it’s offered.

It can exist next to labor, sure, as long as it’s domestic—and done with a smile. It can exist next to sexuality, sure, as long as it’s neither too much nor too little. It can exist next to effort, sure, as long as it’s put into looking modest (ish), manicured, and ideal for male consumption. The Western Feminine, at its core, is unthreatening to the Western Masculine: white women are expected to be non-confrontational, effortless, and, yes, demure. It all leads back to patriarchal control: the younger, smaller, and more naive you are, all the easier for men to force their ideals onto you.

Now, let’s be fair for a minute. The entirety of postcolonial beauty standards and gender essentialism cannot be placed squarely on one popstar’s shoulders.

Sabrina is a relatively short, skinny white woman with a cherubic face. She can’t help the way she looks, and both the narrow definition of femininity and the tropes she’s playing into are, most likely, subconscious. Like most white women, the examples of femininity presented to her generally follow the guidelines of the Western Feminine: Taylor Swift, Brigitte Bardot, Jane Birkin, young Dolly Parton—all of which Sabrina has cited as inspirations. While men invent patriarchy, it’s women who perpetuate it; she is inheriting these patterns, not creating them.

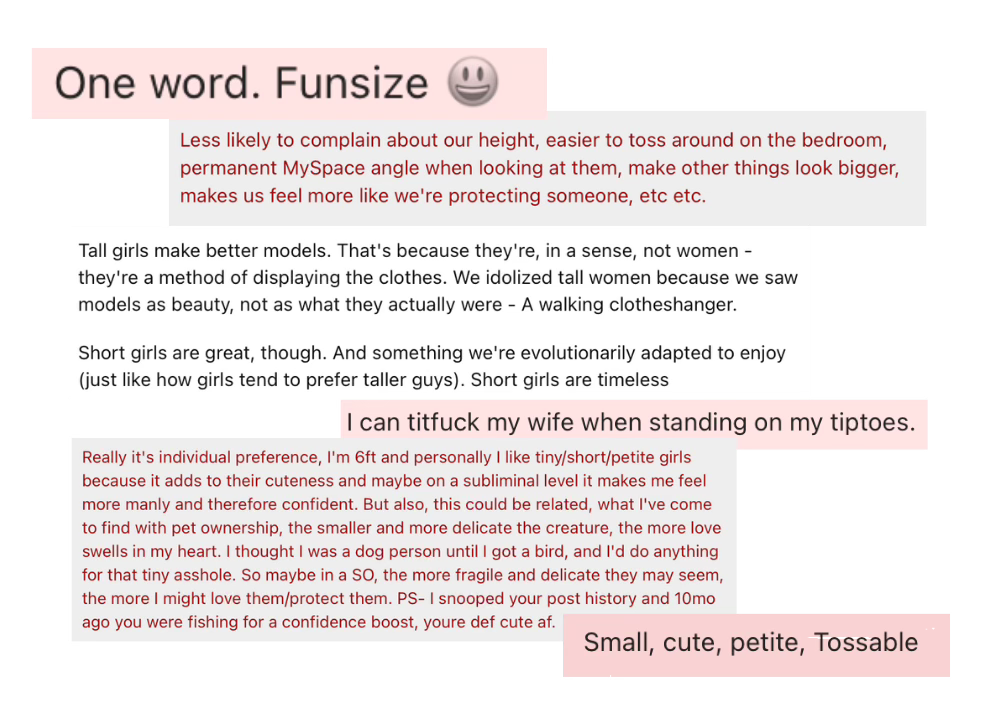

I also believe Sabrina’s stature adds a unique layer to all this. Like I mentioned earlier, Sabrina’s size is routinely mentioned—by her, her team, her interviewers, and her fans—in her core brand. In fact, Short n’ Sweet is meant to be a cheeky reference to her being only 5’. Her smallness only adds to her allure as the Western Feminine, and puts fire behind the pedophilic fantasy her team is selling. But there’s reason for this beyond adherence to American beauty standards—short, white girls gain favor with men because of their smallness.

See below for a myriad of takes in r/AskMen, answering why men go for short and tiny girls:

So, it’s about sex, control, and seeing women as pets—very cool.

Paternalism and dehumanization aside, it’s clear these men see smaller women as more precious, more delicate, more—dare I say it—feminine. Smaller, white women give 21st-century men a taste of the Western Masculine: one where they are the only thing standing between their little lady and a big, horrifying world. It’s power they’re after, therefore it’s power Sabrina wields when using her smallness to market herself.

Pleasing men is strategic under patriarchy, and I can usually find it within myself to understand another woman’s method of survival. I understand why Sabrina feels the need to play with the controlling, semi-pedophilic urges men experience when they see someone like her—especially in a setting which emulates Lolita or Priscilla. In a way, it could be considered powerful for her to articulate this connection for herself, then shit on it by reminding us she’s an adult woman, dammit! Mouse ears, begone: this child star is a big girl, now!

Perhaps that’s the intention behind the juxtaposition of hyper-sexual lyrics with markers of prepubescent girlhood. Reclaiming and expanding upon the label of “horniest girl alive” might feel genuinely empowering to her. That’s fair.

It’s the impact beyond Sabrina that’s dangerous.

What does our sex-obsessed culture do with young people—especially young women? I suggest combing through your own history—that first memory of being sexualized without consent or understanding. Personally, I learned that “kitty cat” meant “pussy” far too soon.

1 in 10 American girls have been catcalled before their 11th birthday. 1 in 6 American girls in elementary and secondary school have experienced sexual harassment. Four in 5 Americans begin having sex before age 20, but 70% of girls age 13 or under report having had sex forced on them. 1 in 9 girls under the age of 18 experience sexual abuse or assault, with girls between 16 and 19 being four times more likely than the general population to experience sexual violence. Teens aged 13 to 19 account for 8% of abortion-seekers in the United States, while burdensome laws requiring parental notification prevent many youth from accessing the abortions they need. Teen girlhood today, while the subject of media fascination and romance, is an existence rife with danger.

The digital world can prove even more dangerous: 1 in 5 preteens report having an online sexual interaction with someone they believed to be an adult. 1 in 7 youths report being solicited for sex online. The number of child sexual abuse material producers sentenced increased by 422% between 2005 and 2019, and in 2023, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children’s CyberTipline received 36.2 million reports of suspected child sexual exploitation online—including more than 105 million images, videos and other files. They also saw an explosion in reports of online enticement: an increase of more than 300% between 2021 – 2023.

This is not a global trend. The US hosts more child sexual abuse content online than any other country in the world, accounting for 30% of the global total of child sexual abuse material as of March 2022. For a country built on Puritan sensibilities, pedophilia runs rampant in our culture. It’s not just the movies, the books, the albums, and the photoshoots. Fascination with prepubescent sexuality has tangible consequences, most of which harm the girls that adult women, like Sabrina, emulate.

Girlhood, by my read, is constraint. Girlhood sits in the audience, watching the world ogle and adore an idea of her—this is the best time of your life, your youth goes so quick, you’ll never be as young and beautiful as you are now—then exits the theater to a world without options. You can’t have free will or personal autonomy—you’re a girl. What you say can’t be brilliant—it’s said like a girl. You can’t skateboard, your soccer team doesn’t have the funding to travel to Nationals, the idiot on your debate team will represent the school, despite the fact that you’ve done most of the work. It’s always the concluding sentence on the other side of disappointment: You’re a girl, you’re a girl, you’re a girl.

Naturally, the promise of womanhood is romanticized for girls growing up under patriarchy, just as the memory of girlhood is for working women. The adult characters of “Girlboss,” “It Girl,” or “Brat” invite a reverence that true girlhood never enjoys; growing up is the opportunity to be taken seriously, to be listened to, to be regarded as something more than a girl. The contemporary rush for young girls to grow up isn’t due to Gen Alpha being more mature; it’s an escape. The hope is: The sooner we become women, the more human we become.

Unfortunately, in a country with abysmal sex education and a foundation of Puritanism, girls see hyper-sexuality as a one-way ticket to womanhood. Experts have noted, along with the exponential rise in requests for online child pornography, that 78% of all web pages actioned during 2022 contained “self-generated” imagery. Most frequently, it is girls aged 11-13 who are self-producing sexual content, usually the result of grooming and coercion by an abuser.

But with the influence of TikTok—a platform well-known for trends meant to demonstrate sexual acuity—access to and the creation of “soft” child pornography is even easier. As adult TikTok users have pointed out, it’s often that the child producing content doesn’t recognize the potential dangers of adults on their account. Reminders to be careful are met with accusations of internalized misogyny or ageism: “It’s just for fun!” “Stop slut-shaming me!” “You’re so narrow-minded!” In their attempt to escape girlhood, youth today are graciously accepting their own exploitation…as long as it comes in feminist packaging.

It’s easier for girls to sexualize themselves when superstars like Sabrina, despite being a decade older, play the role of “sexy baby.” It’s easier to see your prepubescence as a sexual commodity when Lolita, Priscilla, Angela, and the Lisbon sisters inspire male obsession and fantasies. And that’s what all of this is about, right? As Margaret Atwood tells us:

“Male fantasies, male fantasies, is everything run by male fantasies? Up on a pedestal or down on your knees, it's all a male fantasy: that you're strong enough to take what they dish out, or else too weak to do anything about it. Even pretending you aren't catering to male fantasies is a male fantasy: pretending you're unseen, pretending you have a life of your own, that you can wash your feet and comb your hair unconscious of the ever-present watcher peering through the keyhole, peering through the keyhole in your own head, if nowhere else. You are a woman with a man inside watching a woman. You are your own voyeur.”11

If we want to talk capital, then investing in male fantasy will produce the best-possible return. With a current fanbase of 94.9 million people—majority women—Sabrina’s superstardom is only rising, as is her influence and capital gain. Her and her team’s use of pedophilic fantasy in Sabrina’s core brand—while unfortunately, a smart business decision—will have ramifications on the self-imagination of her fans…and beyond.

Her brand is trapped in the ouroboros of feminist sexuality. Balancing the desires of self, hypothetical fans, real relationships, business strategists, and the music industry at large is a Kobiyashi Maru; you can’t win—you’re just eaten. While we’ll likely watch Sabrina get “woman’d” soon, just like peers Chappell Roan and Charli XCX, but I wonder if her proximity to Girl will keep her safer. More precious to all of us.

I wonder if that is the point.

Much of the theorizing here began with my dear friend, Emily, whose dedicated viewing of and musings on Sabrina’s “Nonsense” outros inspired this piece. I love you, Emily! No one is more generative than you.

Quinn Moreland, “Short n’ Sweet: Sabrina Carpenter” (Pitchfork, 2024)

Thanks much to Ijeoma Umebinyuo, whose piece A Short History of the Epistemology of the Soft Girl and feedback added much to this conversation.

Genius Lists, “List of Sabrina Carpenter ‘Nonsense’ Outros” (Genius, 2024)

Lynn Hirschberg, “Sabrina Carpenter Knows She Has You Hooked” (W, 2024)

Carolyn Twersky, “Sabrina Carpenter Wants to Shock You” (W, 2024)

Jade Hurley, “Men in the Feminist Movement: How College-Aged Activists Approach Cis-Men’s Antiviolence Involvement” (George Washington University, 2019)

Caren M. Holmes, “The Colonial Roots of the Racial Fetishization of Black Women” (Black & Gold, 2016)

Black Future Fund, “Ain’t I a Woman?: Blackness and Expansive Notions of Femininity” (Black Future Fund, 2024)

Awo Eni & Jade Hurley, “The IOC Violated Olympians’ Reproductive Rights…and Didn’t Want You to Know About It” (National Women’s Law Center, 2021)

Margaret Atwood, The Robber Bride (1993)

Hi from 2025! You can read my follow-up piece on this essay and continue the conversation below:

A lot of this post was really interesting to read. But as a fellow short woman (5’1”), I found parts of this piece frustrating. I’ve been talked down/condescended/infantilized my whole life due to my height. Are short women with round faces not allowed to be sexual adults? Or am I and Sabrina perpetuating some kind of pedophilic fantasy by simply existing?

Really great insight!!

Any grown person's commitment to pedobait under the guise of the "harmless" coquette aesthetic is very "you either die lolita or live long enough to see yourself become the humbert."